Chapter 6

The next morning, Liza doesn’t feel rested. Her neck aches, and she shivers as she pushes the duvet aside. If she sees Antonio today, she’ll ask whether he managed to sleep at the shelter—until then, she can’t feel at ease. By eight o’clock, she’s cycling across the market toward school. It’s Thursday, and the vendors have already set up their stalls. Most of them are wearing snow boots. A thin layer of snow blankets the entire square, except where the heavily loaded delivery vans have left slushy tracks.

On Thursdays, Liza always finishes school at noon. Before heading home, she stops by the haberdashery stall to help load everything back into the van. The few euros she earns come in handy for buying new sheet music. The market woman is grateful for her help—she hauls crates full of yarn and trims all week and often ends up with sore shoulders. For Liza, the extra money is a welcome addition to the job she has on Thursday evenings and Saturdays at the bakery, housed in an old building along the Market, where the baker and his wife are always glad for an extra pair of hands.

Liza looks around, scanning the fairly quiet market to see if she recognizes anyone. She hopes she won’t see Antonio. If she does, it means he spent the night in the city centre; if she doesn’t, it might mean he’s still sitting at the breakfast table at the night shelter. She silently hopes for the latter.

As quickly as the slippery road allows, she cycles on to school—she hates being late. In the open bike parking area, everything is soaked; the snow clinging to hundreds of bike tires has melted into puddles. She slips inside, hangs her coat on the metal coat racks in the main hall, and heads upstairs.

Outside the classroom, no one has arrived yet, and the bell will ring in two minutes. There’s no point in going back downstairs to the auditorium. She sets her bag against the wall and sits down beside it. Then the swing door to the stairwell bursts open, and Gerard steps into the hallway. He has the same course profile as Liza, so they share all the same classes.

“Hey,” he greets her cheerfully. That’s as far as it goes. He slides down against the wall, too, and stares straight ahead.

“Are you working on Saturday?” Liza asks.

“Saturday?” Gerard repeats, a little absentmindedly. “Oh, right, yeah, I’m working then. You too?”

Liza nods. “Yes. It’s really busy in the shop right now. Probably for you too?”

Gerard nods. “And it’s freezing. I’m already dreading it. You’re lucky you work inside a store. My toes almost freeze off sometimes. They can’t heat the stall too much because it’s bad for the cheese. Only when it’s really cold do they turn on a little heater. At least that helps a bit with your frozen toes and legs.”

“You do wear moon boots, right?” Liza laughs.

“Hey,” Gerard suddenly says, “could I maybe come by around lunchtime to eat my sandwich at your place? I could warm up at the same time.”

“I’m fine with that,” Liza replies. “I’ll just have to ask the baker, but he’s not difficult. I’m sure it’ll be okay.”

Just then, the bell rings, and at that very moment, the teacher comes down the hall, a long string of students trailing behind him. He opens the classroom door, and the students squeeze inside, dropping noisily onto their chairs. The rest of the lesson remains restless. Everyone is hoping for more snow.

“If this keeps up a bit longer, we’ll have a white Christmas,” Mr. Kunst says. “Cozy, isn’t it?”

It is cozy—but Liza can’t separate the cold and the snow from thoughts of Antonio. Her mind drifts again. She imagines herself sitting by the decorated mantelpiece in the living room while, outside, Antonio wanders through the snow in the dark. She sees him coughing, his eyes glowing with fever. How long can someone keep going with a fever before they simply can’t anymore?

The morning flies by, and before she knows it, she’s back on her bike, heading home. She cycles part of the way with Hanneke.

“Did you get the music from Mr. Noot?” Hanneke asks.

“Yes, I picked it up yesterday and played it right away. It’s a really beautiful piece—I’ve been enjoying practising it a lot.”

“I’d actually like to do it too,” Hanneke says, “but I just can’t shake the nerves.”

Liza glances at her from the corner of her eye. She feels that tight knot in her stomach too, sometimes, when she thinks about the performance—about standing there alone with her violin in that big church, all those eyes on her. She knows she doesn’t play flawlessly; a wrong note will probably slip in somewhere. But she doesn’t want fear to take the lead. How could you ever move forward in life that way? You have to take the opportunities you’re given. And an opportunity only truly counts if you have to work for it. How else are you supposed to grow?

At the traffic lights, they each go their own way.

“Maybe I’ll come into town tonight,” Hanneke calls after her. “Grab a coffee at your place.” If it isn’t too busy, they can have a quick chat.

The market is still buzzing when Liza arrives. She parks her bike beside the sewing supplies stall and tucks her bag into a safe spot, where a passerby won’t easily grab it. She really wouldn’t want to lose her phone or wallet. She starts loading the crates that are used the least. They have to go into the van in a specific order so the vendor can set them up again as quickly as possible tomorrow. Within an hour, the entire stall is taken down, and Liza heads home a few euros richer.

Then her eye is caught by the flower stall. This vendor is packing up, too, and loose fir branches are scattered across the ground.

“May I have those branches?” Liza asks, pointing at them. The man recognizes her—he always sees her on Thursdays at the haberdashery stall.

“Oh sure, that’s fine,” he says. “Come here,” he beckons. Liza puts her bike on its stand and walks over to his truck, where he immediately swings out a large garbage bag.

“There’s more loose greenery in here—would you like this too?” he asks.

Liza looks into the bag and sees beautiful fir branches and berries.

“I’d love that,” she replies with a smile. She drags the bag to her bike and plops it onto the rear rack. “Thank you!” she calls back as she pedals straight across the market, over the bumpy cobblestones. One hand grips the handlebars while the other steadies the bag on the back. It isn’t easy, but soon she reaches the brick pavement, where riding is much smoother.

She turns into the church alley and parks her bike at home by the shed door. After putting it away, she heads down the hallway, heavily loaded with the greenery. Her mother never has time to decorate the house for Christmas—that’s always Liza’s job. So far, the only hint of Christmas is the candle holders in the window. Of course, the sexton’s house can’t be left dark during Gouda by Candlelight.

Liza puts her school things away in her room. She quickly eats a sandwich, plays her violin for fifteen minutes, and then does her homework for the next day. Before long, she’s finished and runs upstairs to fetch the crate of Christmas decorations. She hauls it into the kitchen and lifts the lid, letting the little bags of red apples on sticks, the silver baubles, and the golden bells slip through her fingers. There’s also a small bag of miniature Santas.

She remembers buying them at the Christmas market a few years ago. Her mother had said Santa had nothing to do with Christmas and hadn’t included them in the wreaths and garlands she made that year. Liza can still feel the disappointment when she saw the little Santas sink to the bottom of the box. This year, she decides, they will have a place in the garland on the mantel.

For the same reason, the Santas were never used; they also don’t have a Christmas tree at home. “A Christmas tree has nothing to do with Christmas,” her mother always says.

“Oh,” Liza had once asked, “then what do the garland on the mantel and the wreath on the front door have to do with Christmas?”

“Nothing either, but that’s just for the cozy atmosphere,” her mother had replied.

“But a Christmas tree is cozy too, isn’t it?” Liza had dared to ask.

Her mother had grown a little prickly. “All those shiny balls in the tree—totally unnecessary,” she had said.

Liza looks at the little bag of silver mini baubles in her hand. What’s the difference between a big Christmas bauble and a small one? What’s the difference between a big TV and a small one? she immediately thinks. Does it really matter if you have a TV in your room or up in the attic, like Hanneke does at home? It’s all nonsense.

Shrugging, Liza digs further into the Christmas crate. She glances at the kitchen clock—it’s almost half past two. Quickly, she calculates how much time she has left before she needs to start preparing dinner. If she makes something simple, like macaroni, she’ll still have nearly two hours to work on the garland.

She grabs a pair of scissors and starts cutting small pieces of greenery from the bag. Using the little sprigs, she twists them with wire into bunches. A delightful forest scent fills the kitchen. Once she has a whole pile of green bundles, she takes a straw garland and secures the bunches tightly along it with a spool of wire. Working diligently, she continues until a quarter to five, when she pricks the end of the wire into the greenery with a sigh.

So far, she’s quite pleased with the result. She decides to make dinner first, and if she still has time while waiting for everyone to get home, she can attach the decorations afterward.

She chops an onion into the pan, adds a piece of frozen ground beef, and lets it thaw over low heat. Meanwhile, she sets a large pot of water on the stove to heat. Perfect—now she can take another look at the Christmas garland. She picks up the little Santa figurines and arranges them among the greenery, finding spots for the red apples and silver baubles as well. It already looks very cozy.

Still, she thinks it could be a bit more playful. Peeking into the garden, she spots the corkscrew willow and decides to snip a few branches to tuck into the garland. A little while later, a small bundle of curly-willow branches sits in the kitchen.

The ground beef is nearly thawed, and the water for the macaroni is boiling. She drops in a package of macaroni and sets the timer. The beef soon browns and crumbles. Liza stirs in a bag of pre-cut stir-fry vegetables, adds some seasonings, and grabs a generous chunk of cheese from the fridge to mix through the cooked macaroni. A small carton of tomato juice completes the vegetable mixture.

She lets it simmer for a bit and returns to her artwork. Carefully, she pins the little decorations to the garland, and not long after, carries it over to the large white-marble mantel. She drapes it so a section hangs down on either side. Lighting the candles on either side of the mirror above the mantel, she steps back to admire her handiwork. Liza sighs with satisfaction. The candlelight reflects in the mirror, creating a beautiful glow in the otherwise dark room. She takes a moment to enjoy the scene, then switches on the candles in the window as well.

At that moment, the front door swings open. Pierre storms in.

“Hey, that smells amazing! What are we having for dinner tonight?” he calls out, tossing his coat onto the hall rack.

“Macaroni,” Liza calls back.

“Nice work, I have to say,” he says appreciatively, eyeing the garland.

It makes her happy that he expresses admiration—you never quite know what’s going on in his head.

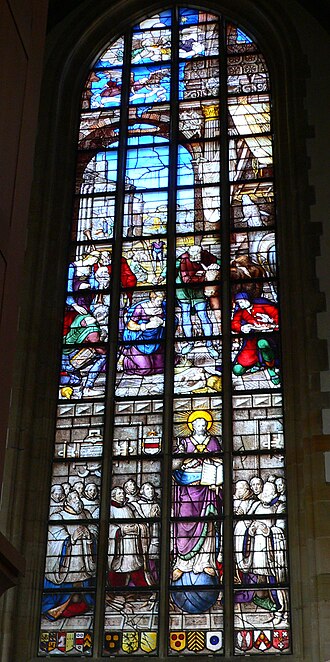

Five minutes later, Mom and Dad come in as well. They offer compliments too. Then everyone quickly sits down at the table, since at six o’clock there’s another tour at the Sint-Jan. Dad needs to be there for the program Gouda Glass in the Spotlight. In the church hall, he will explain the stained-glass windows to tourists, after which someone from the tourist association will take over to show the group the exterior windows. This month, the windows are lit so they can be fully seen from outside in the dark. Walking past the Sint-Jan, it feels as if you’ve stepped back into a medieval city.

“I’m coming along on the tour tonight, Dad,” Liza says. “It’s been so long since I heard your story. I want to see if there’s anything new.”

“Well, you’ll find out soon enough,” he replies. “Someone’s done a lot of research on the windows, so there’s much more known about them than before.”

After dinner, Liza and her parents head across the street to the church. Pierre gets to clear the table and tidy up the kitchen. “I guess I’ll just have to play by the December rules,” he grumbles. He has to work tonight too—serving beers at the Tapperij. Mom and Dad tried everything to change his mind, but Pierre doesn’t mind working in the smoke and listening to the sentimental songs.

Mom stays in the shop by the church while Dad and Liza step through the door into the choir. Inside the church, a small group of about fifteen people is waiting. They’ve turned up the collars of their coats against the cold draft that sweeps through the lofty space. At the back, a chair scrapes across the stone floor, the sound echoing beneath the high vaulted ceiling.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Dad begins, “as the sexton of this beautiful church, I’d like to take you this evening through the world-famous Gouda Glass windows. We’ll start with window twelve.” As he speaks, he leads the group toward it. “This window depicts the birth of the Lord Jesus. It was made in 1564 by Wouter Crabeth. You see Joseph and Mary with the Christ Child.”

The group forms a half circle around him, gazing up with interest at the colourful window towering above them.

“Many artists depict a stable or a cave as the place where the birth took place,” Dad continues. “After all, there was no room for them at the inn. Here, the Christ Child is not lying in a manger, as described in the Bible, but on a sheaf of wheat—a symbol of the Bread of Life, as spoken of in John, chapter 6, verse 41.”

He points upward. “Look—behind Mary, you can see several shepherds, and between Joseph and Mary, there’s a shepherd placing his hand on the head of an ox. Yet the New Testament doesn’t actually mention an ox or a donkey. Their inclusion in the nativity comes from Isaiah, chapter 1, verse 3: ‘The ox knows its owner, and the donkey its master’s manger, but Israel does not know me; my people do not understand.’ As early as the fourth century, the ox and donkey were given allegorical meaning, representing Judaism and paganism. The ox is a clean animal, bound by the Law of Moses, while the donkey is unclean, carrying the burden of paganism. Both animals can be freed from their yoke by Jesus. In the window, the ox is being led toward the Child by a shepherd. According to the glass artist, the donkey—busy eating from the feeding trough—is the less interested of the two in the birth of Christ.”

As she listens, Liza’s gaze shifts from the windows high above her to the group of people, and back again. Suddenly, she startles. Antonio is standing among them. Why hadn’t she noticed him earlier? He’s listening intently to the explanation, his pale face framed by dark curls, eyes lifted toward the glass. They shine, and it almost looks as if he’s crying—or is it the fever still lingering?

The group moves on. Dad continues talking about other windows, but Liza can’t focus on the story. She lingers a little behind the others, hoping Antonio will walk beside her. It seems he hasn’t noticed her at all.

After about half an hour, they arrive back at the shop entrance, where the group is handed over to a guide from the tourist office. Those who have bought a ticket for the extra tour can continue outside to view the windows from the other side.

Liza needs to hurry home now to change so she can be at the bakery by seven o’clock. With the city so beautifully lit, there will surely be plenty of tourists, and her help will be needed. She slips between the people browsing in the church shop, heads quickly down the steps to the street, pushes open the heavy door, and is about to step outside.

“Wait a moment,” she hears from behind.

When she turns around, she sees Antonio coming down the stone staircase.

“I have to hurry—I need to go to work. I’m going to change,” she says, flustered. She can’t stay and talk now, and it wouldn’t be good if her parents saw her with him.

“Okay,” he says. “I’ll wait for you outside. Can I walk with you?”

Liza nods nervously and turns the key in the front door. “I’ll be right back,” she says, closing the door behind her.

Her hands tremble as she puts on her dark red skirt with the white apron. She almost buttons her white blouse and black vest crookedly, but catches it just in time. She quickly runs a comb through her hair, pulls on her coat and boots, grabs her bag from under the coat rack, and opens the front door again. She locks it and immediately starts walking. She still has ten minutes, which she can easily make, but she hates being late. She much prefers arriving five minutes early so she can start calmly.

Antonio is waiting for her, his Santa hat back in place. Liza can’t help but chuckle a little—it actually looks rather silly. Maybe she should find another one for him. Besides, it’s a bit strange to keep wearing it after Christmas.

For a while, they walk in silence.

“Were you able to sleep at the shelter last night?” Liza asks—the question that’s been on her mind all day.

“Yes, it was nice and warm there.”

“Do you still have a fever?” she asks.

“I don’t think so. The medication I got is working well. My friend is getting better too.”

“Thankfully—for both of you,” Liza sighs.

“You don’t have to worry so much,” Antonio says, shaking his head. “I know where to go if I need help.”

Liza shrugs. “It’s just hard to shake it off. I wish I could do something practical to help you.”

“I think there’s an opportunity coming up where you’ll be able to do just that. I’ll keep you posted, okay?”

“Okay,” she says hesitantly, even though she has no idea what he means.

“Your father gave a beautiful explanation about the stained glass of Jesus’ birth,” Antonio continues.

Liza nods. The Sint-Jan stretches overhead, majestic and silent. The windows are clearly visible from the outside. They pass the group they had been with earlier in the church. The guide is enthusiastically explaining the images in the glass. People shiver in their thick coats—you really have to be willing to endure the cold to experience a medieval-style tour. Liza and Antonio walk on. Once they can no longer hear the guide, Antonio continues.

“That ox and donkey your father talked about—neither of them really wants anything to do with Jesus. The wealthy West, the donkey, gets caught up in the atmosphere of Christmas, while the Jewish people, the ox, are still waiting for the Messiah.”

“I think you’re right,” Liza says. “I spent the whole afternoon working on the Christmas decorations for the mantel. I did wonder whether that really belongs with Christmas, but I also wanted to make the house feel cozy.” She hesitates. “Still, what matters most to me is that the Lord Jesus came to save us.”

She wants to say more—to justify herself. Not just to Antonio, who doesn’t have a home to make cozy, but also to God, because she, too, has been caught up in all the decorations that have nothing to do with Christmas.

“Jesus was poor,” she murmurs. “We have it far too good. We don’t understand what it means to leave a rich, warm heaven and choose to be born in a filthy stable.”

Then she falls silent. Maybe Antonio understands much more about this than she does. He surely hasn’t always been as poor as he is now. And he probably didn’t become homeless by choice, the way the Lord Jesus did. She resolves to ask him someday how he ended up in this situation.

Antonio walks with her across the market square. They say goodbye at the bakery, and he briefly takes her hand.

“I’m glad you thought about it.”

His wink makes her happy, and she watches him go with a smile.

“Hey, Liza, you’ve come at just the right time,” Stefany greets her as she walks into the shop. It’s packed with customers. The baker steps to the end of the counter and says quietly, “Could you prepare a box with fifteen pastries and take it across the street to the Tapperij? They’re throwing a party tonight, and with this rush, I really can’t leave.”

The Tapperij? That’s where Pierre works. Couldn’t he have come by himself? Now she has to go into that pub, which she really doesn’t feel like doing. She hangs her coat in the back, washes her hands, and grabs a large box. She arranges a cheerful assortment: marzipan pastries, apple pie, quark cake, cream puffs, and hard mocha pastries, all mixed together. She seals the box with a bakery sticker, rings it up at the till, puts her coat back on, and heads out.

The Tapperij is directly across from the bakery. She walks past the city hall’s sculpted stone entrance and crosses the street. Using her shoulder, she pushes open the café door. Inside, the air is stale. The room is hazy with smoke and smells strongly of beer—just like the pub above Mr. Noot’s place. Liza makes her way toward the bar with the box of pastries, carefully watching her steps—it’s very dark inside. Here and there, stands with electric candles provide a little light, but not much. The floor, walls, ceiling, and even the bar are covered in dark wood paneling.

“How much do I owe you, young lady?” the bartender asks politely. His bald head glows in the soft candlelight.

Liza sets the box on the bar and pulls the receipt from her pocket. The bartender squints to read the amount.

“Well, you see, the pastries aren’t actually mine, but I’ll pay for them this time. I wouldn’t want to spoil an evening for a young couple celebrating being together, right?”

Liza smiles. She has no idea what he means. What matters to her is getting the money. The bartender rummages under the bar and soon places the cash in front of her. Liza quickly counts it—thankfully, it’s correct.

Behind her, the door jingles open. She turns and sees Pierre walk in. Is it that late already? He doesn’t start until half past seven.

“Hey, man,” the bartender greets him. “Your pastries were just delivered by this young lady.”

Surprised, Liza looks from one to the other. Hadn’t the bartender been talking about celebrating a relationship? What does Pierre have to do with that? Is she missing something?

Then a figure emerges from the shadows at the back of the café. It’s a girl with long, dark hair and large, dark eyes. Her denim mini skirt hugs her hips, and the white blouse she’s wearing is cut so low that if she bent over, her navel would show. On high heels, she strides over to Pierre, throws her arms around his neck, kisses him squarely on the mouth, and runs her fingers through his hair.

Liza watches, stunned. Then she makes a firm decision. She walks up to them and holds out her hand to the girl.

“Hi,” she says kindly. “I’m Liza, Pierre’s sister.”

Hesitantly, the girl takes her hand. “Hi, I’m Mira.” She looks at Pierre questioningly. He smiles at her happily, then gives Liza a meaningful look.

“So now we both have a little secret, don’t we?”

For a moment, Liza is taken aback. She nods. Indeed—now they both have a new secret to keep. Things are getting complicated.

“Well, I’d better get going. Have a good evening.” She waves to the partygoers and the bartender. Outside, she gulps in the icy air. The cold still bites. On the far side of Market Square, behind the city hall, an ice rink has been set up over the past few days. The music from the rink blasts in her ears. Confused and still a little shaken, she walks back to the warmly lit bakery.

For the rest of the evening, she stands behind the counter. The baker serves customers who come in to warm up after shopping in the cold. She doesn’t see Hanneke. She would love to tell someone about tonight, but there’s no one. Next Friday, Leonora will be coming—she can tell her then. Another whole week to wait. How am I going to get through it?